Neurodiversity: The Problem of Autism as Identity

In honour of Autism Awareness/Acceptance Month, let’s begin by asking a simple question:

What is autism?

Unfortunately, the answer to this simple question is more complicated than expected. Below is the dictionary definition:

Oxford Dictionaries define it as: “A developmental disorder of variable severity that is characterized by difficulty in social interaction and communication and by restricted or repetitive patterns of thought and behaviour.”

The Autistic Self-Advocacy Network (ASAN) defines it as: “Autism is a neurological variation that occurs in about one percent of the population and is classified as a developmental disability.”

On the surface, it would seem like the two definitions are similar. However, they could not be more different. The dictionary definition seems to be based on the diagnostic criteria for autism spectrum disorder. The ASAN definition is based on the concept of neurodiversity.

What is neurodiversity?

Judy Singer, the originator of the term “neurodiversity”, defines it as: “Neurodiversity for me is the timeless and incontrovertible reality that every single living being is unique, and that no two human minds, (actually mind-body complexes), are the same.”

I agree with her. Everyone is unique. What she has said is clearly a fact of nature. So what’s the problem? The problem comes when people start to associate natural with valuable.

“Neurodiversity is a natural and valuable form of human diversity,” Nick Walker states. His opinion is so respected that it appeared in an editorial published in a peer reviewed journal. But there is a flaw in this neurodiversity paradigm. The flaw is this: just because something is natural does not make it valuable.

The concept of value is relative. What might be valuable to you might not be valuable to me. A $100 bill might be valuable to someone who only has $100, but it is less valuable to someone who has $100,000,000.

I would assume that neurodiversity is meant to be valuable to the person who is neurodiverse. It wouldn’t make much sense otherwise. But neurodiversity is not always valuable. Take Spinal Muscular Atrophy (SMA) for example. It is an inherited condition (i.e. natural) that affects motor neurons. If you take the literal meaning of “neurodiversity”, meaning neurological diversity, then SMA would be part of it as it affects neurons. Unfortunately, it is also the leading genetic cause of infant deaths. SMA has zero value to someone who dies from it. But it could be argued in a perverse, roundabout way that the effort to cure SMA is advancing our understanding of genetics and is therefore valuable to humanity.

Is diversity itself valuable? There is such a thing as too much diversity, as evidenced by the introduction of rabbits Down Under. Instead of increasing biodiversity, rabbits became a significant contributor to species loss in Australia instead. Attempting to increase diversity without taking into account the balance of a system is just reckless.

So, what is autism?

Nick Walker states that “autism and other neurocognitive variants are simply part of the natural spectrum of human biodiversity, like variations in ethnicity or sexual orientation (which have also been pathologized in the past).”

It seems to me that subscribers to the neurodiversity paradigm also tend to view autism as an identity. And if autism were an integral part of a person, like ethnicity or sexual orientation, then any attempt to research its cause and treat its symptoms would be impossible. It would be like trying to cure homosexuality or Asianness.

But this view also creates problems. When asked to define autism, most people who view autism as an identity tend to give an answer that is similar to the definition given by the Thinking Person’s Guide to Autism (TPAG): “Autism is a naturally occurring human neurological variation and not a disease process to be cured.”

The problem with the phrase “Autism is a naturally occurring human neurological variation” is that it is essentially meaningless. Isn’t every human being in the universe a “naturally occurring human neurological variation”?

“Autism is a neurological, developmental, and pervasive way of being,” Chrysanthe Tan wrote. Even though I understand each individual word, I cannot understand what she is trying to say when she puts these words in this particular order. What exactly is a neurological way of being? A developmental way of being? A pervasive way of being?

“I was going to write about what autism is, but as I wrote it transmogrified into what autism isn’t,” Rhi wrote in a blog post.

It seems to me that one of the problems with viewing autism as an identity is the inability to provide a coherent definition.

In fact, most definitions of autism as identity describe its cause first (genetic, natural, etc.) before going on to describe a set of behaviours. ASAN’s definition lists the following: Autistics have different sensory experiences; non-standard ways of learning and approaching problem solving; deeply focused thinking and passionate interests in specific subjects; atypical, sometimes repetitive, movement; need for consistency, routine, and order; difficulties in understanding and expressing language as used in typical communication, both verbal and non-verbal; and difficulties in understanding and expressing typical social interaction.

In short: Autistics see/hear differently; learn and problem-solve differently; think with deep focus and develop passionate interests in specific subjects; move atypically and sometimes repetitively; need consistency, routine, order; have difficulties understanding and expressing language and social interaction. In the end, the most sensible way to define autism is as a set of behaviours.

Viewing a set of behaviours as an identity can lead to its share of problems as well. For example, statements like “If you love and accept your autistic child, you can’t hate #autism. You can’t.” only make sense when autism is an identity. Contrary to what Rachel said to Bruce in Batman Begins, people are not solely defined by what they do. People who punch someone else while undergoing a tonic-clonic seizure aren’t guilty of assault. It’s understood that they aren’t responsible for their behaviour while having a seizure. The person they are underneath, the intention behind the actions, matters.

So what really is autism? I think the definition by Autism Speaks (AS) is the best one so far. They state that: “There is no one type of autism, but many. Autism, or autism spectrum disorder (ASD), refers to a broad range of conditions characterized by challenges with social skills, repetitive behaviors, speech and nonverbal communication.”

There is a lecture from Elliott H. Sherr, MD, PhD, from the Institute of Human Genetics at UCSF available from Youtube.

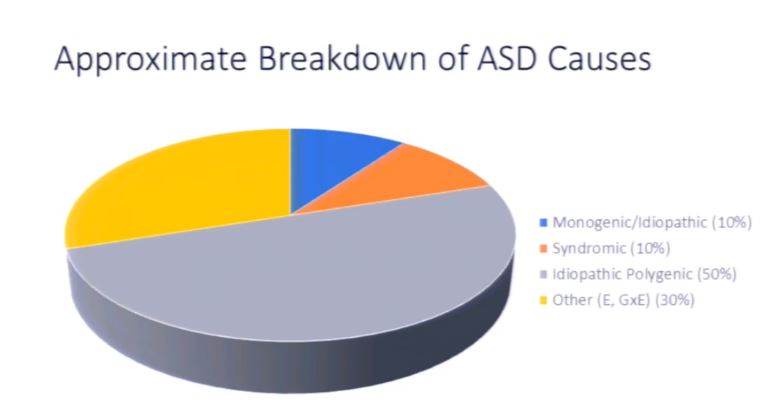

There is a chart in the video, showing the many different causes of autism, which I have screencapped and put below:

Each category represents lots of different causes. Just to give you an idea, according to SFARI, at least 84 different genes have been implicated in causing autism that are also part of a syndromic disorder, which is only 10% of the pie chart.

A majority of cases are idiopathic. Basically, science still has no idea what exactly is causing a majority of autism cases. And while a majority of autism cases are caused by genetics, there are environmental causes too. Whether it is purely environmental or a combination of environment and genetics, these make up 30% of the pie chart.

AS has made it its goal to seek the causes and types of autism, with the goal of translating these discoveries into personalised treatments. As one of the largest funders of autism research in the U.S, it can help advance our understanding of autism. And I think everyone can agree that understanding is the first step towards acceptance.

Tragically, TPAG tells its readers not to support AS, because AS does “causation- and prevention-oriented research”. ASAN published flyers telling people not to donate to AS as well, saying that only a tiny portion of its budget goes towards helping autistic people and their families. In doing so, ASAN ignored the entirety of AS’s science expenditure. Why? I don’t know. Maybe because if autism were an identity, then any attempt at treatment would be a personal attack.

In 2014, 15 infants underwent gene therapy for SMA. As of Aug 2017, 100% of them were still alive, compared to a historical 8% survival rate.

Gene therapy might be able to help autistic people whose autism stems from a monogenic or syndromic cause, who also tend to be on the severe end of the spectrum. But, if autism is an intrinsic quality of a person, akin to ethnicity, then gene therapy would be eugenics. The concept of autism as identity is untenable. This is neurodiversity eating itself.